If you shoot nonreactive (fixed) steel targets regularly where frangible ammunition is not required (it rarely is) or the steel has been shot a great deal (it usually has), you likely have been hit by ricocheting bullet or jacket fragments. My experience suggests one is usually hit from the shots of others, and to a much lesser extent from reactive steel. (Ricochets also occur in indoor ranges when shooting paper targets, due to walls, floors, and metal objects downrange, or backstop integrity issues). Ricochets can be large, sharp, and travel at sufficient velocity to pierce skin and draw blood, sometimes even through a layer of clothing. A bullet or jacket fragment can become embedded in an open wound at skin level or deeper, and can cause most types of wounds; laceration, incision, avulsion, or puncture. A puncture wound (also referred to as penetrating trauma) is the type most likely to do damage beneath the skin and require professional medical attention even though superficial bleeding is stopped. I have seen each of those type wounds, and one likely arterial and two venous bleeds caused by fragment ricochets.

I have been hit by ricochets dozens of times. Twice the result was a bit more than merely a superficial laceration needing a Band-Aid®. My small immediate action Individual First Aid Kit (IFAK) and my rather comprehensive large backup medical kit were each easily up to the task. I also once suffered a high speed penetrating wound as a result of an out of chamber detonation while unloading. The wound did not bleed much, so I sensed there was something lodged beneath the skin. My self-diagnosis was correct; a piece of razor-sharp cartridge brass (about the size of a small pinky fingernail) went into my abdomen about two inches below the sternum and lodged anterior to my liver. It could not be seen by inspection of the rather small open wound; it was visualized by CT scan. Out of fear that it would move and cut my liver, a quite serious, possibly life-threatening occurrence, I was transported from a hospital ER by EMS to a Level I trauma center where I was admitted as a GSW and underwent laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia to remove it.

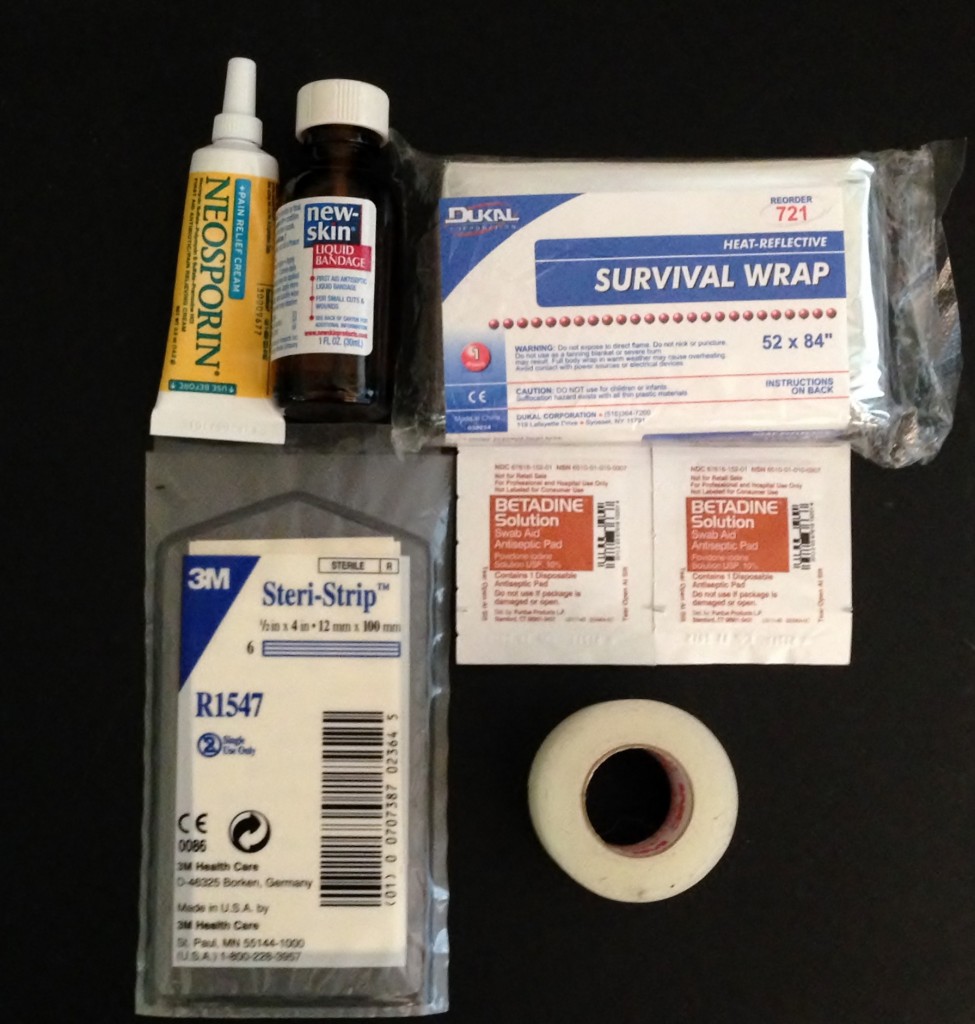

I have implemented some precautions and wound treatment protocols as a result of my own experiences and after seeing and attending to others who were injured by ricochets. I wear higher than standard rated full coverage ballistic eye protection, long standard weight pants, layered shirts, one with long sleeves and collar, and a hat. I keep my tetanus vaccination current. I carry a clean cloth or package of 4×4 gauze sponges in a pocket, a small IFAK of my own design with me to or near the line, and keep a larger, complete medical kit nearby which has additional wound care items and duplicates of bandages and gauze materials for wound compression and packing. Some of the individual medical products I use are pictured above.

A complete IFAK or “blowout” bag which contains sufficient materials for field application to the kinds of wounds you might incur shooting steel are sold ready-made. If you carry a prepackaged kit, also carry Band-Aids®, extra gauze products, and medical tapes. (Scott Ballard reviewed the Dark Angel kit in a prior MSW post).

I ask a “reliable” (someone who can stand the sight of blood, preferably with advanced first aid training) buddy in advance to monitor me if I suffer a wound (other than a minor one) from a ricochet. If I ask for assistance, or appear unable to properly and fully attend to my wound, the buddy is instructed to follow these protocols adapted from what I know about basic wound first aid and the concepts of TCCC:

- Glove up. Gloves are nitrile, long cuff, textured, not powdered, not sterile.

- Put me seated or prone wound side up, far away from possible further ricochet injury. Deploy ground cover such as hypothermia foil blanket, dog “wee-wee” pad, or painter’s absorbent drop cloth. (These are useful as a drape, in assessing and monitoring blood loss, providing a clean field on which to put arrayed treatment items, and to promote easy cleanup). Take out all of my items that are likely to be used.

- If necessary, cut away clothing area larger than the size of the wound (do not use your folding knife, use seat belt cutter, safety hook, or EMT shears).

- Irrigate the wound with wound saline; visually inspect.

- Fabric or other debris or jacket or bullet fragments visible on the surface should be removed with forceps or tweezers (first disinfect with antiseptic solution or alcohol or iodine swab patch).

- Flush with antiseptic wash.

- Assume I am on a blood “thinner,” or anti-coagulant (numerous prescription drugs have that as an intended or side effect), aspirin, NSAID, or nutritional supplement (fish oil, niacin (vitamin B3), vitamin E) that can delay proper hemostasis (the clotting process).

- Stopping the bleed as fast as possible is the number one priority. The more acute the blood loss, the sooner you must do something to promote hemostasis. Apply direct pressure with clean (sterile/packaged preferred for layers that are in direct contact with the wound) pressure dressings (4X4 wound pads, rolled gauze, surgical pad, special battle trauma material, and compression or elastic rolled bandage) as appropriate for site/size of wound. My large medical kit contains two or three times as many of those items as would likely be needed. In the case of a large wound or surprisingly large volume or rapid blood loss, especially if the blood loss appears to be arterial (spurting or pumping) or venous (dark in color, steady flow), cover with extra layers of pads. Apply direct manual pressure for ten (10) minutes. (Head, face, and neck wounds will likely bleed profusely even if the wound is small). Pressure should be applied continuously without interruption for inspection, and with force sufficient to cause minor discomfort. Use hemostatic dressing as first layer or impregnate first layer with agent (powder) on any wound that is bleeding more than a small household cut would. (The agent’s packaging should be retained in the event professional medical care is later necessary). Do not disturb/remove existing layers if blood soaks through; add more layers on the outside.

- I do not provide direction for the use of a tourniquet. Nor, a Halo®, HyFin™, ACS™, or Vaseline® impregnated gauze to occlude (seal) an open chest wound, since those resources would almost never be indicated for a bullet or jacket fragment ricochet, they require a higher level of training, or introduce the distinct possibility of complication.

- If the bleeding is arterial, causes a large hematoma (bleeding under the skin), does not slow almost immediately after pressure is properly applied, or stop completely after ten (10) minutes of constant pressure, if I am not completely responsive, appeal prodromal (that is, exhibit two or more signs of shock, or impending or actual loss of consciousness, which may be a result of vasovagal syncope), call EMS for transport to a hospital ER.

- When bleeding has completely stopped, carefully wash off excess agent from surface with wound saline and dry. Apply sterile adhesive bandage (I carry several different shapes and sizes, including waterproof and extra adhesive varieties), surgical strips, butterfly closures, and cover dressing, or skin glue (“liquid bandage”), as appropriate. (I should be able to self-apply or provide instruction to my buddy at this stage).

- In the event of a head or facial wound, protect eyes from blood and other fluids (with gauze pads or other covering) during treatment. If a ricochet fragment has entered an eye opening, irrigate with eye wash solution and inspect. If there is blurred vision, bleeding, or if discomfort is not completely resolved by irrigation, cover eye with pad and tape in place. Call EMS or arrange for private transport to eye-hospital ER.

I recognize and accept I will usually be my own first responder and often the most knowledgeable on scene person. However, I am not a physician or certified EMT, and avoid playing one on the range or elsewhere. So, I ran my protocols by a friend who is a tactically oriented physician with ER, TCCC, law enforcement occupational, and wilderness medical training and experience. He (Fabrice Czarnecki, M.D.), added the following commentary: (1) irrigation and assessment may need to be deferred in order to address bleeding; (2) probing a wound or removing foreign bodies below the skin requires skill and one must be careful not to aggravate the wound using an instrument which might cause blood vessel or nerve injury; (3) EMS or private transport to a hospital ER is likely indicated if the wound is other than minor and the person is over 50 or has any complicating medical conditions (pulmonary, cardiac, diabetes); (4) it is important to seek follow-up medical assessment from your doctor within 24 hours if you do not go to the ER, to determine the presence of foreign bodies in the wound or internal injury, and to treat possible infection with prophylactic antibiotics which require a prescription; (5) keep the wounded warm while awaiting transport to the ER, and; (6) every shooter should get advanced first aid training which includes study of the TCCC educational materials (linked above). Thanks, doc.

Speaking of TCCC – if you have not taken a TCCC based trauma aid course and are present where firearms will be discharged, you need to learn basic battlefield care (including “care under fire” if you go in harm’s way). I recently watched “Combat Lifesaver,” a Panteao Productions video, as a basic TCCC refresher. Doc Spears (of EAG staff) simplifies most everything and is an easy-going, first-rate instructor who will keep your attention. I found his demonstration of what various blood loss volumes look like and the related discussion especially helpful. The video trailer is here.

Now, I am off to study the material and products in the above hyperlinks, to reassess my medical kit, and to repackage items in use specific sub-assemblies.

Stay safe and keep your blood on the inside where it belongs. But if you cannot, keep your wounds clean, dry, and covered.

Excellent post.

Good stuff any time you are out at the range, steel or no steel. I have had fragments come back at me out a well used dirt backstop….

Very good post!! I do pretty much the same thing but fortunately have not been hit by a ricochet. (just the whole bullet… Long story…. 😉

Excellent post. We all need to remember what can happen on the range and be prepared for it. Great work!

Sorry but I have to repeat what has been said above; Excellent piece!

I will put together a kit for my range bag. Thanks

A few comments, based on shooting at the Rogers School, which is exclusively a steel target program.

They absolutely forbid JHP ammo, because of the danger from sharp pieces coming back. In recent years, they have gone to requiring TMJ ammo, which in their experience significantly reduces injury from splash back. I think they consider traditional ball ammo to be closer to TMJ than JHP, but released their prohibition on regular ball last year, because of the ammo shortage and thei inability to get TMJ ammo.

How common is this really? I have been shooting for about 5 years now, altogether maybe 40-50 range trips, which I know is not that many. But I have never seen a ricochet, let alone anyone get hurt. Ranges have had differing rules. One range didn’t allow JHP or magnum calibers indoors, but had outdoor booths. And my favorite local one requires a minimum of 50yds for rifle, 100 yds for rifle ground targets. But people shoot at the pistol range with ground targets spitting distance. Is that something to be cocerned about? No metal targets or steel ammo (unless raining) at that range unless cowboy action (fire risk). But at the other locl range they have plenty of steel targets, but 35 yds is the minimm for handguns/rimfire, 100 yds for rifles. Is there any risk at that distance?

Yes, ricochets are extremely common when shooting steel targets, and Steve is specifically citing some matches where pistol steel targets are as close as 10-15 yards. Your examples cite more distant steel targets or targets made of wood/paper, where ricochets are either mitigated somewhat by distance or not a factor due to the target material.

Not common in many places, but common in venues where one or more of the following exist: Pistol stages where steel is at 11-20 yards; well shot steel; no ammunition restriction; multiple shooters engaging steel simultaneously in the same square range; dozens of on deck competitors standing within 20 feet of the line. Regardless of probability, I think safe is better than sorry. I expanded the medically oriented discussion to provide information for other than ricochet injury.